Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Salzburg-100: Don Giovanni

Зальцбург-100: Дон Жуан

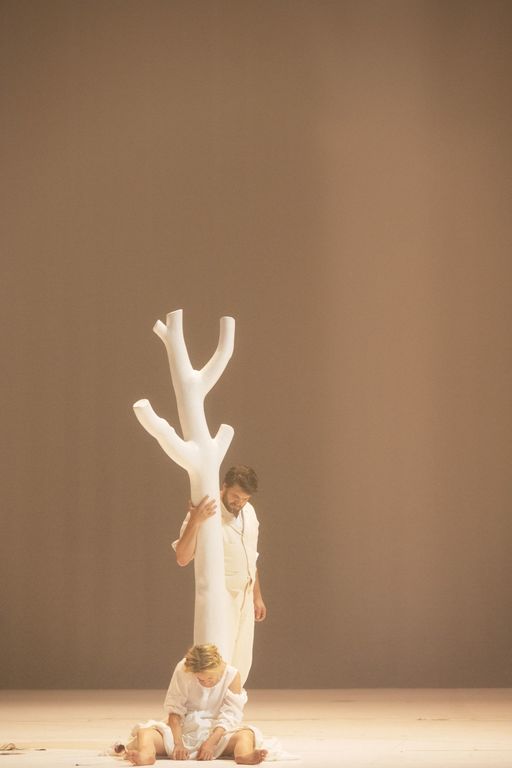

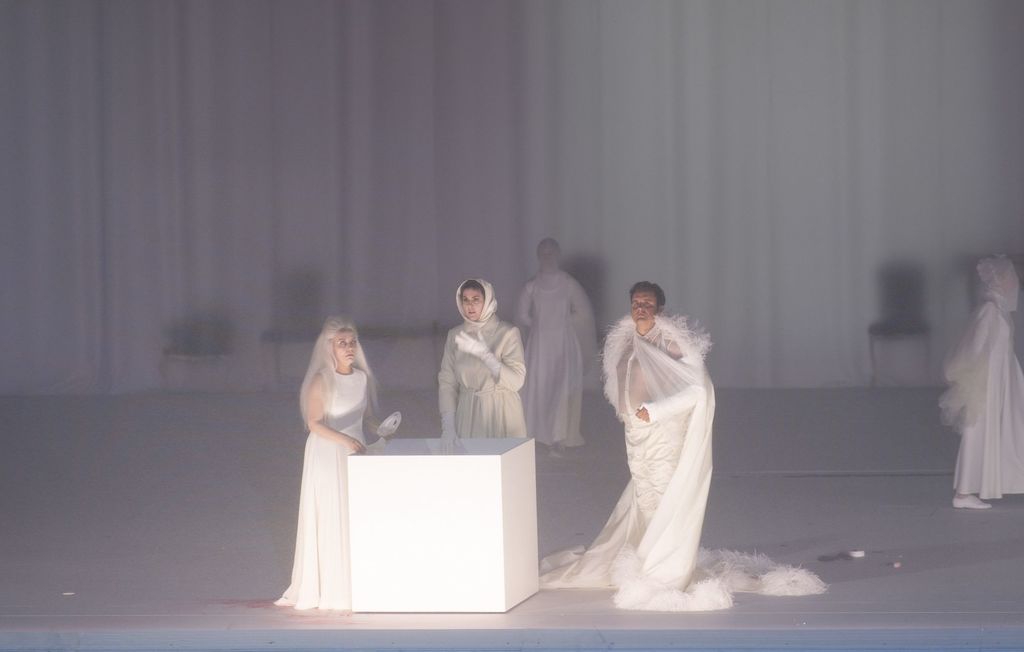

Romeo Castellucci will develop his production in a process of continuous exchange with conductor Teodor Currentzis. The figures around Don Giovanni must be grasped in their sharply contrasting characters and musical physiognomies as well as in their individual relationships to the protagonist, without denying the comic element of this dramma giocoso.

During the course of the action Castellucci will charge the neutral dramatic space with a series of precise connotations resulting from his deep excavations of the work.

Actors

Don Giovanni

Donna Elvira

Donna Anna

Leporello

Masetto

Commendatore

Crew

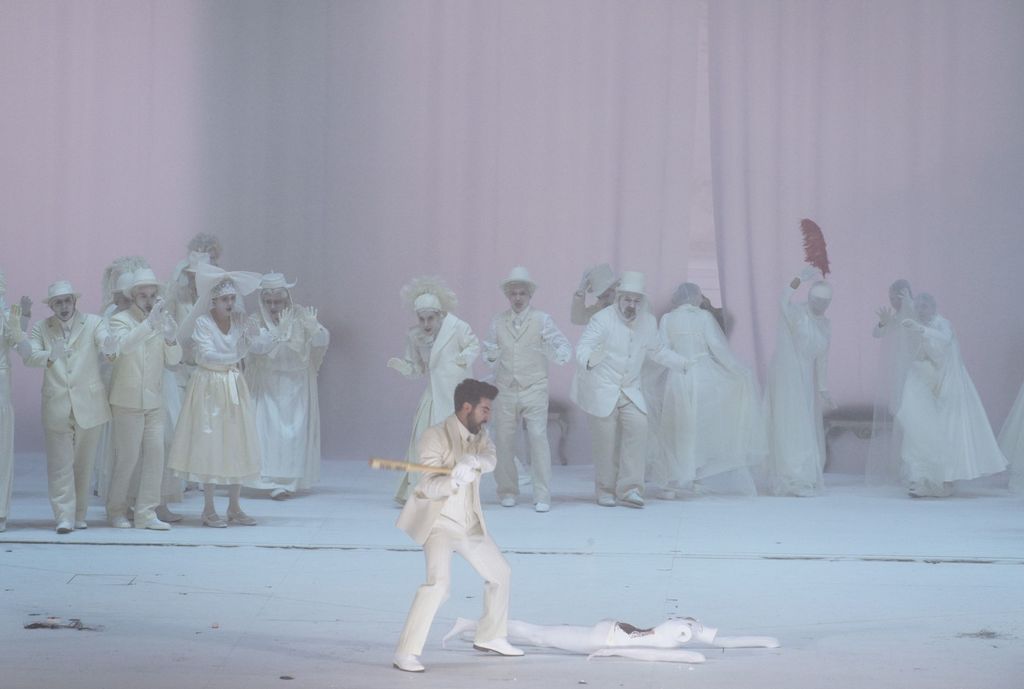

For Romeo Castellucci, approaching Don Giovanni means facing up to the ambiguity and complexity as well as the inner disequilibrium with which Mozart imbues the protagonist of his opera. Vitality and destruction: in this essential ambivalence Castellucci sees one of the fascinations of this figure. Wholly bound up in the moment, Don Giovanni’s life force is embodied with symbolic pregnance in the almost obsessive headlong spate of the ‘Champagne Aria’ ‘Fin ch’han dal vino’. This forms the frenetic prelude to a party that will be open to all — and whose true purpose Don Giovanni announces quite blatantly: Leporello, his manservant and antithetical alter ego, will subsequently be able to add another ten names to the lengthy list of Giovanni’s female conquests. Dedicated to the pleasure principle, his existence, which knows neither rest nor reflection, drives Don Giovanni to ceaseless seduction — a desperate compulsion beyond pleasure, reflecting awareness of his own mortality. Of death.

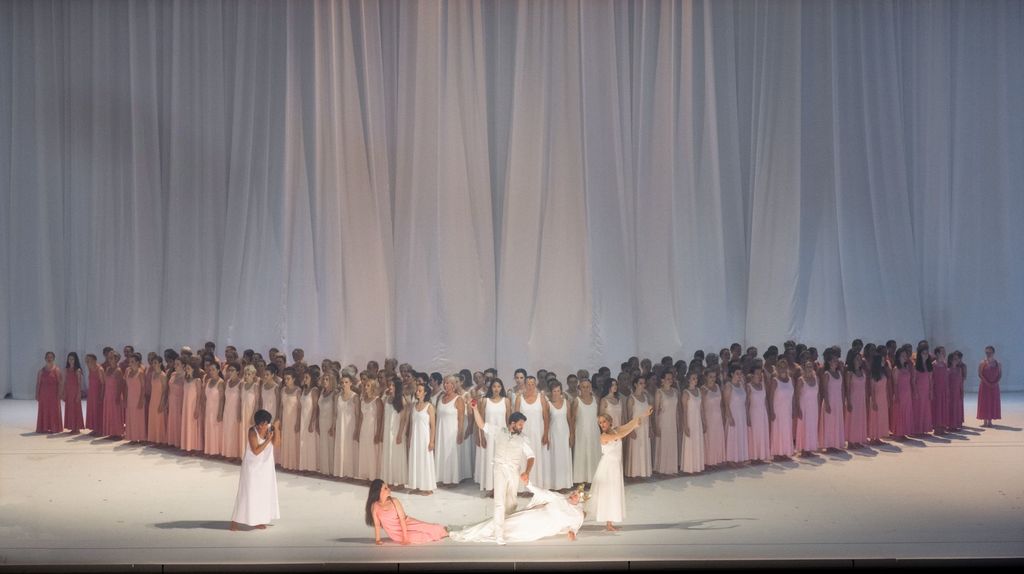

Mozart’s Don Giovanni was described by Kierkegaard as the spirit of sensuous desire, as ‘flesh incarnate’. His life realizes itself in pure immanence, beyond good and evil. That makes him highly dangerous. Don Giovanni does not acknowledge any rules of social coexistence; he recognizes no law — whether the law of morality, justice or religion. He rebels against the Law of the Father. Although he represents a smouldering energy that magnetizes the people around him and sets them in motion, Don Giovanni isolates himself radically from society (albeit not without exploiting his privileged status). He brings confusion, chaos and destruction to everything he touches. The dancing at the party he throws is to be ‘without any order’, as it says in the ‘Champagne Aria’ — and Mozart takes Don Giovanni at his word: in the finale to Act I, the overlayering of various dance movements even briefly leads to a collapse of the musical structure.

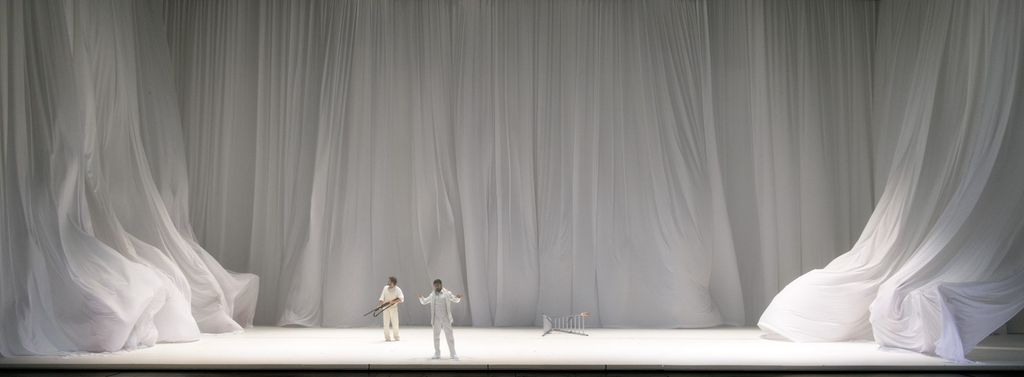

In this context the opera’s original main title assumes deeper connotations, in that the word ‘dissoluto’, here meaning a dissolute person or rake, also signals its etymological derivation from ‘dissolvere’ — and indeed, Don Giovanni leads a life ‘dissolved’ from any ties to human, let alone higher rules. Even more, he is someone who actively loosens, separates and divides. Following Don Giovanni’s attempt to ravish Donna Anna under cover of darkness, the opera’s introduction ends with the killing of her father, the Commendatore. Now for the first time society turns against the culprit — soon to be identified by Donna Anna — with a call for vengeance. However, he will be ‘punished’ (‘punito’) — as in Tirso de Molina’s Catholic morality play El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra, which marks the birth of the Don Juan figure in the early 17th century — not by human agency but by a supernatural power, namely the Commendatore, who returns as a statue, as the ‘stony guest’. This irruption of transcendency will only seem disproportionate to those who see Don Giovanni solely as the roguish seducer to which Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto tends to reduce him. But Mozart opens up abysses and dimensions of tragedy and anarchy, from the very first moment: the beginning of the overture anticipates the music of the ‘stony guest’, the dialogue between the Commendatore and Don Giovanni, ‘in which even the most matter-of-fact listener is carried to the limits of human imagination and beyond; where in sight and sound we apprehend the supernatural’ (Eduard Mörike in Mozart’s Journey to Prague, tr. L. von Loewenstein-Wertheim).

Romeo Castellucci will develop his production in a process of continuous exchange with conductor Teodor Currentzis. The figures around Don Giovanni must be grasped in their sharply contrasting characters and musical physiognomies as well as in their individual relationships to the protagonist, without denying the comic element of this dramma giocoso.

During the course of the action Castellucci will charge the neutral dramatic space with a series of precise connotations resulting from his deep excavations of the work.

Mozart’s Don Giovanni was described by Kierkegaard as the spirit of sensuous desire, as ‘flesh incarnate’. His life realizes itself in pure immanence, beyond good and evil. That makes him highly dangerous. Don Giovanni does not acknowledge any rules of social coexistence; he recognizes no law — whether the law of morality, justice or religion. He rebels against the Law of the Father. Although he represents a smouldering energy that magnetizes the people around him and sets them in motion, Don Giovanni isolates himself radically from society (albeit not without exploiting his privileged status). He brings confusion, chaos and destruction to everything he touches. The dancing at the party he throws is to be ‘without any order’, as it says in the ‘Champagne Aria’ — and Mozart takes Don Giovanni at his word: in the finale to Act I, the overlayering of various dance movements even briefly leads to a collapse of the musical structure.

In this context the opera’s original main title assumes deeper connotations, in that the word ‘dissoluto’, here meaning a dissolute person or rake, also signals its etymological derivation from ‘dissolvere’ — and indeed, Don Giovanni leads a life ‘dissolved’ from any ties to human, let alone higher rules. Even more, he is someone who actively loosens, separates and divides. Following Don Giovanni’s attempt to ravish Donna Anna under cover of darkness, the opera’s introduction ends with the killing of her father, the Commendatore. Now for the first time society turns against the culprit — soon to be identified by Donna Anna — with a call for vengeance. However, he will be ‘punished’ (‘punito’) — as in Tirso de Molina’s Catholic morality play El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra, which marks the birth of the Don Juan figure in the early 17th century — not by human agency but by a supernatural power, namely the Commendatore, who returns as a statue, as the ‘stony guest’. This irruption of transcendency will only seem disproportionate to those who see Don Giovanni solely as the roguish seducer to which Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto tends to reduce him. But Mozart opens up abysses and dimensions of tragedy and anarchy, from the very first moment: the beginning of the overture anticipates the music of the ‘stony guest’, the dialogue between the Commendatore and Don Giovanni, ‘in which even the most matter-of-fact listener is carried to the limits of human imagination and beyond; where in sight and sound we apprehend the supernatural’ (Eduard Mörike in Mozart’s Journey to Prague, tr. L. von Loewenstein-Wertheim).

Romeo Castellucci will develop his production in a process of continuous exchange with conductor Teodor Currentzis. The figures around Don Giovanni must be grasped in their sharply contrasting characters and musical physiognomies as well as in their individual relationships to the protagonist, without denying the comic element of this dramma giocoso.

During the course of the action Castellucci will charge the neutral dramatic space with a series of precise connotations resulting from his deep excavations of the work.

Christian Arseni, Piersandra Di Matteo

Translation: Sophie Kidd